By Maria Miranda on Fri 26 September 2025 in Insights

The UK’s Invisible Air Quality Problem

Proper ventilation is essential in all buildings, but none more so than in our own homes.

Research shows that people spend around 90% of their time indoors, where air quality can be up to 3.5 times worse than outdoors. The rise in working from home arrangements has contributed to this, with more people than ever spending their working and home lives within their own four walls.

When ventilation is inadequate, the air inside homes can become stale and humid. Moisture builds up, encouraging mould, mildew, and damp to spread. These conditions can damage building infrastructure, while also impacting resident health, contributing to respiratory issues, allergies, and mental wellbeing challenges.

Alongside this, homes are exposed to a range of pollutants, with sources including fuel-burning combustion appliances, building materials and furnishing, and household cleaning products.

As a result, the air quality in our homes can often be far from satisfactory, and a silent contributor to long-term illness and disability.

Millions of people across the UK are inadvertently suffering ill-health effects from poor air quality in their homes – yet it remains to be taken seriously as a health factor.

This report will examine the current state of residential air quality standards across England, while exploring what action needs to be taken to ensure health and living conditions are considered in future building and development plans.

The report covers:

- The current state of damp housing in England

- The importance of ventilation in homes

- Health and wellbeing impacts of damp and poor ventilation

- Structural factors contributing to damp housing

- Energy efficiency in houses with damp

- Recommendations for developers

Key Findings

- 1.3 million English households are living in damp homes.

- 1 million children live in damp homes.

- Households with inadequate ventilation are 12x more likely to have damp (60% vs 5%).

- Nearly half (47%) of damp homes contain someone with a health condition — up from 33% in 2013.

- Damp households face higher energy bills: £1,918 per year on average vs £1,648 in non-damp homes.

- People in damp homes report lower life satisfaction (6.8 vs 7.5) and happiness (6.9 vs 7.5).

- Private renters and social tenants are twice as likely to live in damp homes (9%) compared with owner-occupiers (4%).

The scale of the problem

Damp is on the rise across England. A dwelling is assessed as having a damp problem where any of the following exist: penetrating damp, rising damp, or extensive patches of mould growth on walls and ceilings and/or mildew on soft furnishings.

Data shows that the proportion of households affected by damp fell slightly between 2013–14 (4%) and 2018–19 (3%), before climbing again to 5% in 2023–24 — a relative 25% increase in a decade.

Today, that translates to 1.3 million households living with damp problems.

The factors behind this rise are complex. COVID-19 may have impacted households’ abilities to treat damp issues effectively, due to maintenance work being delayed under social distancing measures. The rise in energy costs over this time period has also made it more difficult for households to effectively heat their homes, contributing to increased damp levels.

Damp is most prevalent in private rented accommodation (9%) and local authority housing (9%), with housing association and owner-occupied housing lying at 5% and 4% respectively.

Larger households are most at risk of damp, with 1 in 10 four-person households living in damp homes, compared with 4–5% of smaller households.

Homes with uninsulated solid or cavity walls were also found to be more likely to have damp problems present (8%) than in homes with insulated solid or cavity walls (3%).

Ventilation: The invisible factor

The underlying causes of damp are not always obvious, and while there is an established relationship between damp and energy efficiency, it can be caused by a multitude of factors.

Namely, inadequate ventilation is identified as one of the most common predictors of damp in a home.

Just under 236,000 (1%) English dwellings were found to have inadequate ventilation. Of these, 60% had damp problems, compared with only 5% of homes with adequate ventilation.

Even when structural conditions are sound, poor airflow allows moisture to build up indoors , particularly when homes are overcrowded.

Nonetheless, disrepair factors also contribute significantly. When cold air enters a home without adequate ventilation, condensation and damp accumulate. Additionally, disrepair to external fabric elements of the dwelling can lead to water ingress and penetrating damp to roofs or walls.

12% (3 million) of homes report having an external element in poor condition (chimneys, roofs, walls, windows, doors), rising to 14% of private rented dwellings. Around 15% (453,000) of these homes also have damp.

Meanwhile, damp is present in 19% of dwellings with internal disrepair. Damaged heating systems are shown to be a major contributor to damp; homes with heating systems in disrepair were over twice as likely to have damp (23%) as those with only kitchens/bathrooms in disrepair (10%).

Houses were found to be more likely to have damp present in bathrooms, bedrooms and living rooms (2.1-2.3%) than in kitchens (1.6%) and circulation spaces (0.9%), owing to the increased humidity and reduced air circulation.

Who is most at risk?

Vulnerable and low-income households are most exposed to damp, thus being at greater risk of illness caused by poor air quality.

470,000 vulnerable households currently live in damp homes, with 1 million children living in damp properties.

Elderly people are also at risk, with 324,000 people aged 65+ affected by damp living conditions.

Households in the lowest income bracket with health conditions are more than twice as likely to have damp compared to the highest bracket (54% vs 23%)

Private renters and social tenants are hit hardest: 9% of both groups’ homes have damp present, compared with just 5% of housing association dwellings and 4% of owner-occupied homes.

Nearly a quarter (24%) of households containing someone on a waiting list for social housing are found to live in a non-decent home, with 17% living in a home with damp.

Health and wellbeing consequences of damp and poor ventilation

Poor ventilation and damp directly impact the health and wellbeing of occupants. Moisture supports mould spores and dust mites, which can trigger asthma, allergies, and respiratory issues.

47% of households with a long-term illness or disability live in damp housing – up from 33% a decade earlier.

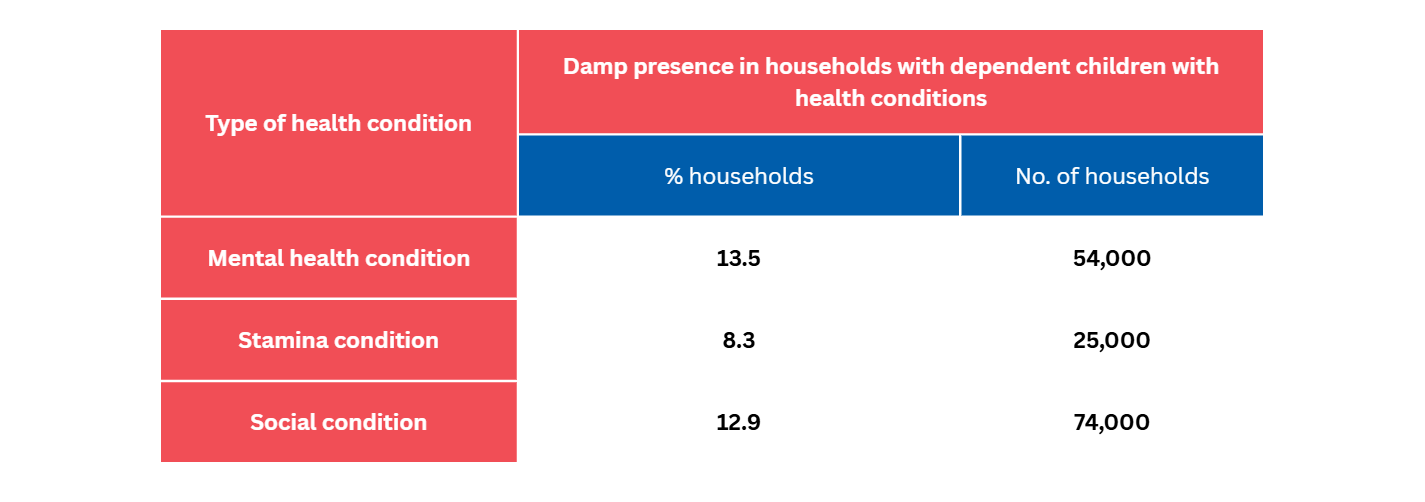

Children are particularly vulnerable: 23% of households with at least one dependent child with a health condition live in damp homes, versus 20% in non-damp homes.

8% of households with at least one dependent child with a stamina condition live in damp households – displaying a clear link between the presence of damp and respiratory conditions.

Meanwhile, 14% of households with at least one dependent child with a mental health condition live in damp households, along with 13% of households with at least one dependent child with a social condition.

In total, there were around 534,000 households with dependent children living in damp homes. Of those, 122,000 had a child occupant with a health condition. Across tenures, there was a significantly higher proportion of children with a health condition living in damp social sector housing (42%) compared with damp private sector homes (18%).

The link is clear: damp housing is damaging to health, especially for children and the elderly.

On top of this, damp doesn’t just affect physical health — it erodes overall wellbeing.

People in damp homes report lower life satisfaction (6.8/10 vs 7.5/10), while also reporting lower happiness levels (6.9/10 vs 7.5/10).

This reinforces the fact that air quality is not just a technical issue, but a quality-of-life issue.

Energy efficiency & costs

Ventilation and damp are closely tied to how energy is used in homes. Damp walls lose heat faster, and residents often reduce heating to save money, worsening condensation.

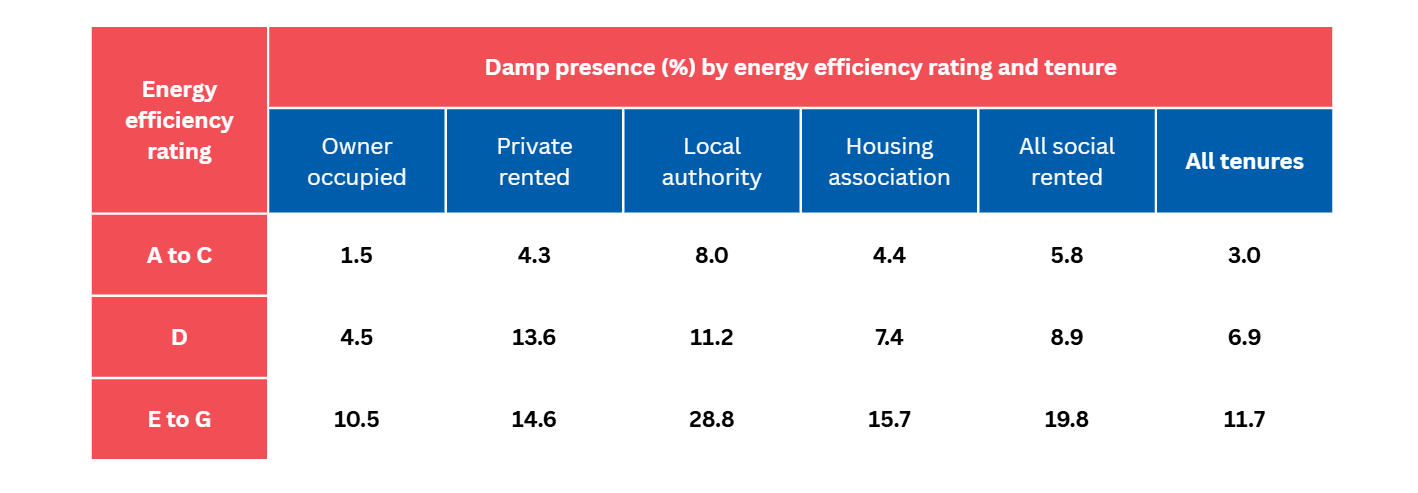

Homes with the poorest energy ratings (E–G) are four times more likely to have damp than the most efficient homes (A–C).

As a result, damp households spend £270 more per year on energy bills (£1,918 vs £1,648), with damp owner-occupiers paying the highest average costs (£2,376 per year).

For households looking to cut down on spending in response to rising living costs, they run the risk of promoting damp.

Households that are reducing their heating (6%) or limiting their energy use (6%) are more likely to have damp in their home compared with homes that are not reducing their heating (4%) or limiting their energy use (5%).

What needs to be done?

The Government stipulates minimum requirements for domestic ventilation, laid out in the Building Regulations 2010. They dictate that all buildings in England should protect the health of occupants by providing adequate ventilation.

For residents in social housing and rented accommodation (statistically shown to be at greater risk of damp) it is the council and landlord’s responsibility to ensure proper ventilation.

In March 2019, the new Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act required all landlords to ensure that their properties are ’fit for human habitation’, which means they must be safe to inhabit without posing any risk to tenant health. Accordingly, landlords have important legal obligations to fulfil regarding indoor air quality.

The surest way to prevent damp is by mitigating both current and potential causes of moisture in a home. This means monitoring high-risk areas such as bathrooms, kitchens and windows, where there are high levels of moisture. If water vapour and droplets in these spaces come into contact with a cold surface (like an uninsulated external wall), this creates ideal conditions for mould to grow.

A properly ventilated space prevents mould from taking root and reproducing – by removing moisture from the air. Achieving a constant airflow into and out of a house means moisture can be dispelled quickly.

In the UK, where seasonal weather conditions can be adverse and simple solutions, such as opening windows, are not always an option, mechanical ventilation systems should be considered.

Considering effective ventilation in early-stage housing development

New-build housing developments are now urged to implement effective ventilation in the initial planning stages, in order to meet increasingly stringent regulations to counter damp and mould later along the line.

With cases of ill-health caused by damp and mould beginning to be taken more seriously by lawmakers, it is in developers’ interests to factor smart ventilation into their plans from the get-go. New regulations, including Awaab’s Law within the Social Housing (Regulation) Act, will require social housing landlords to adhere to strict time limits to address dangerous hazards such as damp and mould in their properties, or risk unlimited fines.

As a result, tenants will be better protected from damp-induced health issues, alongside creating more sustainable and compliant housing for the future.

Prioritising air quality as a health factor

Damp and poor air quality are often dismissed as minor inconveniences, but the data show otherwise. They are public health risks, financial burdens, and social inequalities hidden from public view.

Moreover, the UK’s invisible air quality problem is getting worse: more households are affected by damp today than a decade ago, and the health consequences are reaching the most vulnerable first.

By ensuring homes are properly ventilated, we can reduce health risks linked to damp and mould, improve comfort and wellbeing, lower energy bills by making homes easier to heat and support a healthier, more resilient housing stock.

Methodology

To calculate damp prevalence in English housing, we analysed data on over 16,300 dwellings, along with over 7,500 physical surveys and 200 surveys of vacant dwellings, from The English Housing Survey (EHS) 2023-2024 (released 30 January 2025).